Interviewer: Do you think that if you had paid for the train your life would have been entirely different?”

JG: Listen, do you believe in God?

Interviewer: Sometimes.

JG: Well, ask him. Ask him if my life would have changed – I don’t know.

The psychological consultation can easily take the form of this kind of journalistic interview. The question-answer sequence, in which the client’s life becomes an object of knowledge and scrutiny, can start to feel and sound like an interrogation process. The therapist, as interviewer or interrogator, asks questions of the client with specific ideas and answers in mind. We have preconceived ideas about how the world works and how a person is psychologically formed by their choices and experiences. These ideas shape the questions we ask. There is often the absence of a genuine question mark at the end of our questions. They are more often statements than questions. In some cases, they can even be surreptitious accusations of having made wrong choices, had wrong feelings, or come to failed conclusions. In a BBC interview with the writer, playwright and “Saint” of French Existentialism, Jean Genet, in 1985 (soon before his death) – Genet is able to “break the order of things” (as the interviewer puts it) in this question answer process. Genet was first incarceration in Mettray, one of the most severe reformatories in France, at the age of 15 (until the age of 20). This was the first of many imprisonments. Even though he was already in a habit of thieving, the offense at the time was not having a train ticket. At the onset of the interview, he is asked about the “feelings” of his childhood – of not having parents. A particularly psychologised line of questioning. Genet refuses to take up any lines in this psychological script for how we assess our lives:

JG: You are asking me to tell you my feelings as a child. To speak of them in a satisfactory way. I would have to begin a kind of archaeology of my life, which is absolutely impossible. All that I can tell you is that the memory that I have of it is of a difficult period, certainly. But, in escaping the family I also escaped from family feeling- the feelings I might have had for a family, or the feelings they might have had for me. And so, I am entirely detached, and I was as a child, from any family sentiments. And, it is one of the virtues of the French Public Assistance, which certainly brings up children fairly well and stops them from attaching themselves to a family. Which is, in my opinion (the family that is) probably the first criminal cell.

I am not sure if I would describe Genet as having been brought up “fairly well” but do we even know what that means? He questions here whether the very institution of a family is a good place to be brought up. You could perhaps say that his entire life, his creative works, are a challenge of normative ideas. Genet may represent the possibility of something outside the “incarcerating” ways that we conceive of things as supposedly “normal”. Or, perhaps, he is a genuinely traumatised man lost in his own defences? Genet goes on to describe the relationship between the incarcerated: some inmates were appointed as authorities (elder brothers) over others, a relationship of dominance and submission, that was overseen by the warders.

JG: If you like, the warders were the first audience and we were the first actors, and they enjoyed the pleasure of looking on.

Ironically, the interview process mimics a scene of dominance and submission, being enjoyed by an audience. Dominance of interviewer (on behalf of society) over interviewee (who refused to play by the same rules) and enjoyed by myself (the audience) who now becomes the warder. I become complicit in the act of objectifying Genet as a thing to be known and judged for the life he has led, looking for psychological explanations for who and why he is how he is. A mirror of a scene from Abert Camus’s The Outsider.

This is a position of onlooker is made readily available to us these days through the psychological and psychiatric ideas that have made there way into our everyday thinking and language. We have become the onlookers of war, poverty and and the marginalised. The supposedly well-meaning idea of “mental health” (and therefore, illness) is simply another form of marginalisation. Psychological ideas and explanations of who, how and why “they” are serve as distancing practices that keep you over there and me, safely, over here. Genet manages to address this in in the interview in a language that suggests we are all disempowered by this dynamic: both interviewer and interviewed, jailers and jailed. He questions who has the “right to speak”, and when? What are they allowed to say? On the second day of his interview, he addresses the 7 people hidden from camera:

JG: I had a dream last night. I dreamed that the technicians of this little film revolted. While they’re taking the shots of this film, they never have the right to speak; how does that come about? And I thought they might have enough guts to push me out and take my place. But, nevertheless, they are not moving. Could you ask them how they explain that?

Interviewer: Yes. How they…

JG: How they explain this..,why they don’t come and push me out, and you too…and say ‘It’s so stupid what you’re saying and that I don’t want to carry on with this work’. Ask them.

Interviewer: Yes certainly. Because they don’t speak French.

The interviewer goes on to translate Genet’s utterances from French to English (in a much-abbreviated fashion). The crew fumbles with answers as the camera haphazardly moves off Genet. Part of the interrogation was about Genet’s choice to distance himself from society. At this moment, Genet turns the interrogation onto the film crew and, in doing so, illustrates how it is these kinds of conventions, of treating people as objects to be known and questioned, that are actually the distancing and marginalising practices.

Interviewer: But does it interest you to break the order of things, since you were dreaming about it, do you want to break the order in this room?

JG: To break the order?

Interviewer: Yes.

JG: Of course. It seems so rigid – I am all on my own here and in front of me are 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, people. Of course I want to break the order. That’s why yesterday I asked you to come sit here [points to the chair he is sitting in].

Interviewer: Is it like a police interrogation?

JG: There is that about it, yes. I told you. Is the camera rolling? [Looks at camera man] Good. I told you yesterday that you were behaving like a policeman and you’re carrying on like that now, this morning. I’ve told you that yesterday, and you’ve already forgotten. Because you’re continuing to interrogate me, exactly like the thief I was thirty years ago was interrogated by the police. [Gestures towards the rest of the room] By a squad of police. And, I am alone on this little chair, being questioned by lots of people. There is the norm on one side, where you are: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 [pointing at people behind the camera] and elsewhere, the editors of the film and the BBC, and then there is the margin where I am [pointing to his chair] where I am marginalised. If I am afraid to join the norm, then so be it.

So often, the psychologist or psychiatrist sits on the side of the supposed “norm” and the client or patient sits on the other side – the margin – awaiting judgment. Let us rather talk in equal turns, side by side. Neither of us marginalised by an imaginary audience with criteria for who and how we should be. What would such a therapy look like? Free from interrogation. You shouldn’t need a ticket for the destination that is your own life.

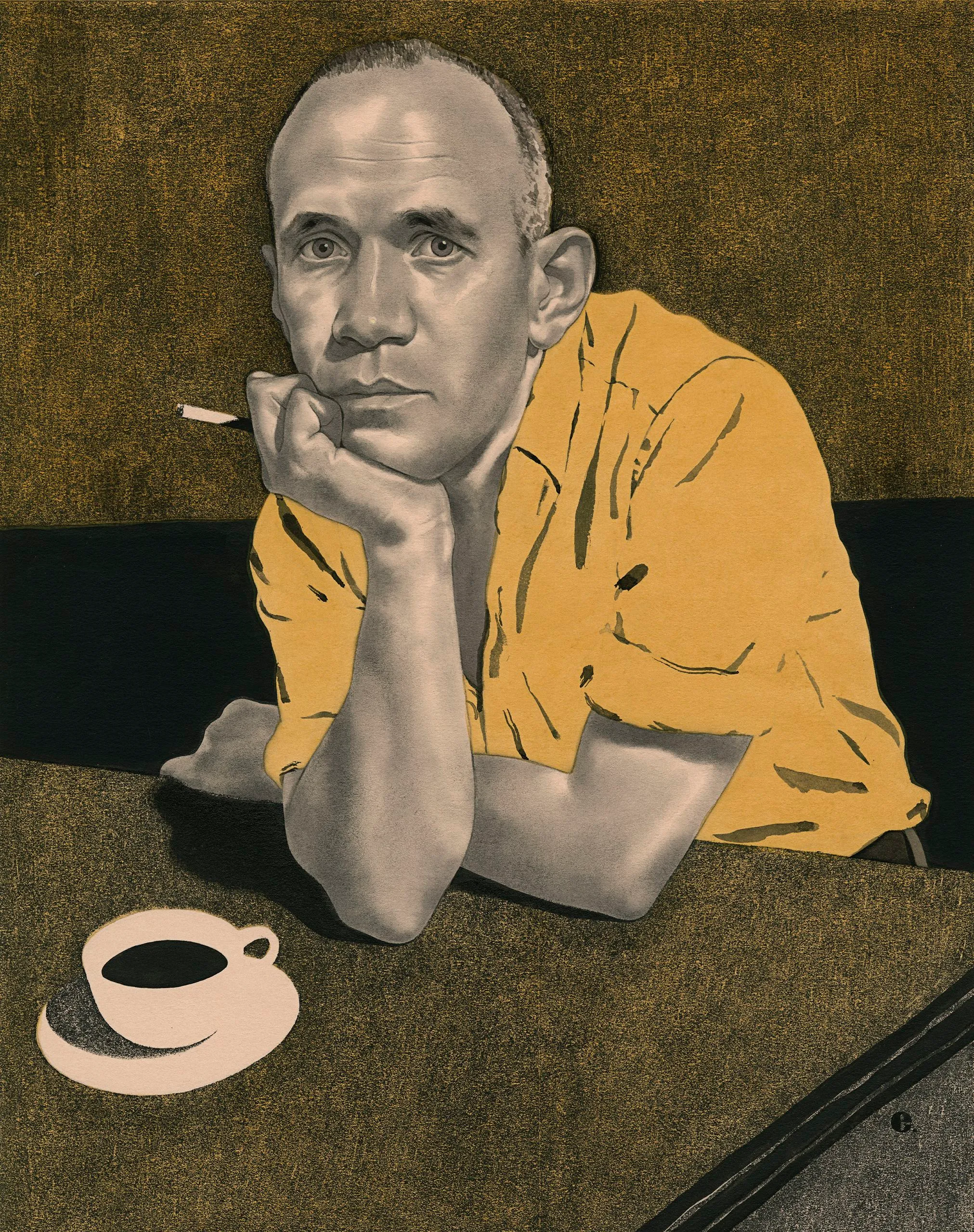

[Image used above is an illustration of Jean Genet, by Edward Kinsella, from an article in the the New Yorker]